What are Flexible Manufacturing Systems and How Can You Use Them?

What are Flexible Manufacturing Systems?

Flexible manufacturing systems (FMS) are designed to allow manufacturers to make sudden changes to production plans. In contrast with mass production on a traditional production line, the goal is easy adaptation of a manufacturing process at any time. This can range from producing brand-new products to modifying batch sizes to simply reordering the assembly sequence. There are two main areas of flexibility: Routing Flexibility and Machine Flexibility.

Regardless of category, FMS works through three main systems:

- Central Control Computer

- Material Handling

- Work Machines

Originating in the 1950s by industrial engineer Jerome H. Lemelson, the earliest iteration of FMS was to incorporate robot-based manufacturing onto factory floors. Today, industrial FMS can be described as any interconnected system overseen by computers from start to finish. This production method is as automated as possible in order to reduce labor and increase production opportunities.

Examples of Flexibility

What is Routing Flexibility?

Routing Flexibility is how well your FMS and machine tools are able to adapt to the production of new products. It can also refer to making any changes to the order of operations necessary for completing production on a particular part.

For example, a furniture company might always install chair legs before adding seat cushions. One day, they were short on material for the legs due to a delayed delivery. To keep up production volume, the cushions are added first so the chairs will just need legs to be completed. In this case, rearranging the assembly sequence is routing flexibility. All the involved machine tools are still performing the same basic tasks, just in a modified way, in order to keep production moving despite the material shortage.

What is Machine Flexibility?

In FMS, Machine Flexibility refers to the use of multiple CNC machines to perform identical tasks. Additionally, this determines the system’s overall ability to make changes to volume or capacity. The idea is to prevent a factory from becoming hyper-specialized to the point that adding new products would require entirely new equipment and facilities.

For instance, machine flexibility would be programming multiple machines intended for certain tasks with additional functionality. If a primary machine needs maintenance, others can pick up the slack instantly rather than causing downtime. And if there is a sudden increase in customer demand for a particular product, more machines can be used to produce the necessary parts with a significantly shorter lead time than using one dedicated machine.

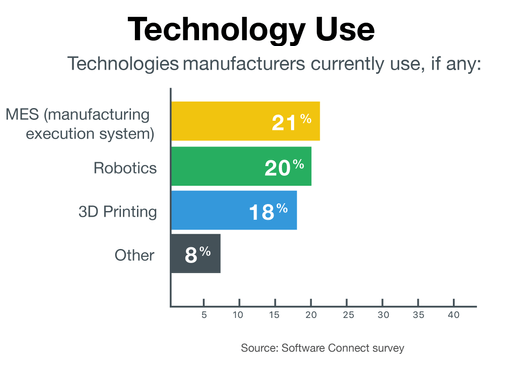

The use of technology, ranging from traditional lathes to 3D printers, has increased the need for computer-integrated manufacturing systems in order to keep production running smoothly.

What are the Three Main Systems of FMS?

The three systems of FMS organize production flow as follows: Work machines, particularly large-scale Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines, have their flow controlled by a Central Control Computer, which is influenced by material handling or the flow of parts.

Types of FMS

- Dedicated: Manufacture a limited mix of parts in high-volume

- Engineered: Manufacture only the same parts, always, to maintain high-quality results

- Modular: Switches between the other 4 types to produce a wide variety of parts

- Random: Parts are processed in an entirely random order determined by what is needed at the time

- Sequential: Parts are processed in small batches in a certain order based on the assembly of the product

A modular FMS offers the most flexibility, though each type offers its own advantages. Multiple types can be used simultaneously, depending on the needs of your production line.

Benefits of FMS

Implementation of FMS at your facility can lead to a lot more production flexibility. Yet there are other major benefits:

Reduce Costs Long-Term

Real-time manufacturing flexibility can significantly reduce total manufacturing costs associated with downtime. If a piece of equipment is down for regular maintenance or emergency repairs, you can keep production moving. Material shortage? You can accommodate this by rearranging the assembly process. Tight turnarounds? Existing machines can be turned from their usual tasks to completing the necessary work.

Reduce Downtime

Instead of using an assembly line, FMS often utilizes pallets to move work-pieces between separate workstations. This means a quality issue arising in one area of production won’t shut down the entire line, as the single impacted pallet can be moved to the side to address the problem as work continues.

Lower Labor Costs

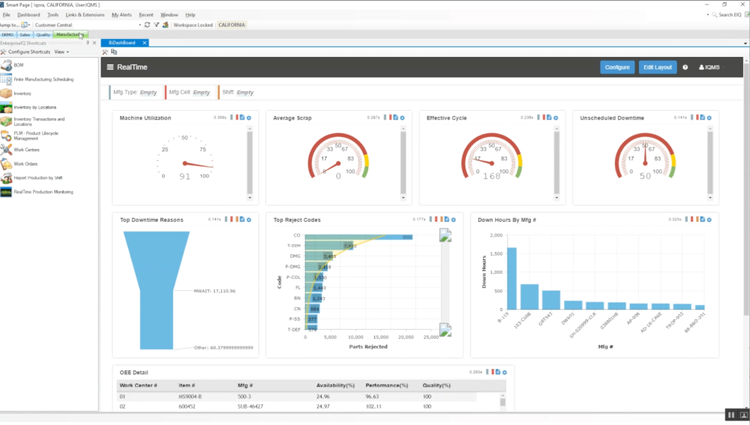

Finally, modern manufacturing methods which utilize automation can lead to lower labor costs. Machines can handle the workload of a dozen workers in a fraction of the time. And cloud-hosted computer-integrated manufacturing can be controlled from anywhere in the world, allowing management to oversee multiple facilities simultaneously.

How Does Flexible Manufacturing Compare to Other Methods?

Flexible manufacturing systems are sometimes described as make-to-order production since both methods allow for sudden product customization. FMS offers additional customization options which may not be attainable with other methods of production, as the production line can be changed at any time to accommodate new products.

Unlike lean manufacturing, which is aimed at reducing waste created during production, flexible systems are focused on allowing for changes. This adaptability is crucial for any manufacturing which wants to adjust production rate to meet customer demand as close to real-time as possible.

Challenges of Flexible Manufacturing Systems

High Up-Front Costs

Since flexible manufacturing systems rely on automation, they are increasingly expensive to set up. And with such a heavy focus on machinery, they are equally expensive to maintain. You need to do extensive pre-planning if you want to lower costs in the long run with FMS.

Machine Overuse

Machine flexibility, which encourages using the same machinery to perform multiple tasks, can lead to equipment overuse. This can also impact product quality, as some machines might not be best at completing parts they were not intended to make. And while this flexibility can cut down on total employees necessary to run the equipment, you’ll need particularly skilled workers to deal with the problems each machine may encounter.

Volatile Supply Chains

Additionally, make-to-order strategies can backfire: failing to meet customer demands can lead to lost sales. While forecasting failures can lead to over and understock, accurate predictions can result in tighter margins. Incorporating some degree of demand planning into your FMS production volume can alleviate some of the potential stock issues. Another option is to consider flexible manufacturing cells, or FMC, in which you utilize FMS practices on a smaller scale.