The Manufacturing Jobs of the Future

What impact is new technology having on manufacturing jobs in the U.S? Recent software innovations, from material requirements planning (MRP) to manufacturing execution systems (MES) software, have revolutionized the daily operations of manufacturing businesses. The rise in automation is also fundamentally changing the nature of manufacturing jobs.

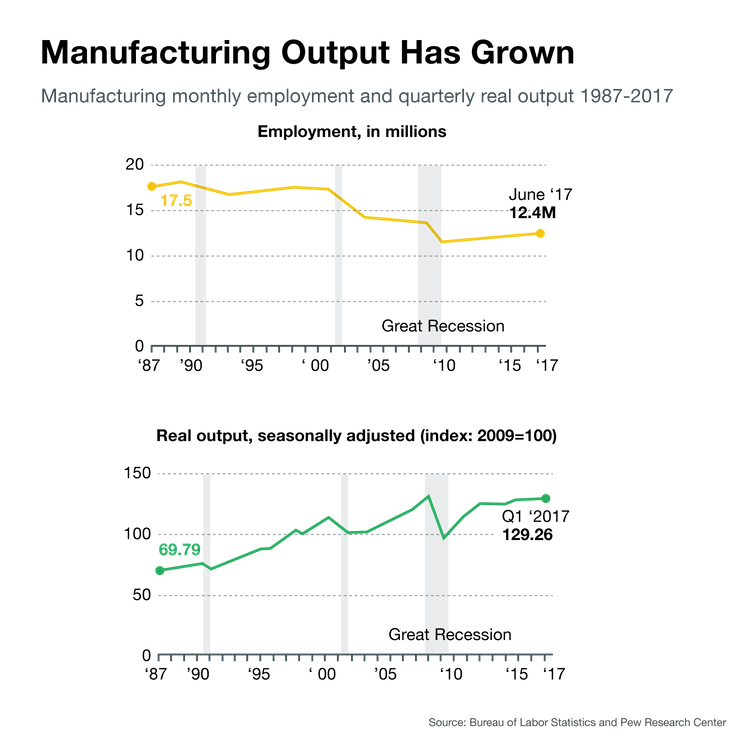

America’s manufacturing workforce is moving through a major transformation–and adaptation is needed in order to survive. According to the Pew Research Center, overall employment in manufacturing stands at its lowest level since before the U.S. entered World War II. From 2000 to 2010 alone, the U.S. lost 5.7 million manufacturing jobs, with stepped-up global competition, weak consumer demand, and improved productivity (such as advanced technology) being identified as the culprits. In the ensuing years, manufacturers have collectively ramped up hiring, adding hundreds of thousands of jobs but coming nowhere close to erasing the earlier losses.

In the midst of our technological revolution, many manufacturing workers fear their jobs will disappear, and in some cases their fears have become reality. To be sure, some manufacturing jobs have been shipped to countries like Mexico where labor costs are cheaper, but many experts point the finger at high-tech automation for the death of most traditional manufacturing jobs.

Still, manufacturers in the U.S. continue to hire workers–often not in traditional roles, but rather in tech-oriented ones.

The manufacturing workforce in the U.S. actually is growing, although not as robustly as the workforces in some other sectors, most notably healthcare. The manufacturing sector added 156,000 jobs from November 2016, when industry employment hit a recent low point, to October 2017, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Among the manufacturing segments picking up the most employees were electronics, chemicals, and fabricated metals.

“While there are still some significant challenges ahead, the outlook [for the manufacturing workforce of the future] is strong despite the obvious concern of robots displacing jobs,” according to contract manufacturer Flex. “The bulk of automation is used for work that would be considered unsafe or impossible for humans. This makes robots a complement to, not a replacement for, human workers. Because of robots, we’ll be able to increase our output.”

It’s worth noting that half of the manufacturing processes at Flex are now fully automated.

So, what will the manufacturing jobs of the robotic future look like? This report will examine the outlook in detail.

But first, let’s visit the factory workforce of yesterday.

Manufacturing Jobs of the Past

Based on figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and other sources, we get a clear sense of the types of manufacturing jobs that have gone away (or are going away).

“Particularly vulnerable are jobs with decent pay that require less than a college degree. And even a bachelor’s degree is no longer a guarantee of success: The greatest job growth over the next decade will be in occupations requiring a graduate or professional degree,” according to The New York Times.

Manufacturing jobs that are particularly vulnerable include fabricator, assembler, machinist, and quality control inspector–hands-on, blue-collar jobs that increasingly are being replaced in the U.S., partly by offshoring but largely by automation. In the glory days of these jobs, robots were nowhere to be seen on factory floors.

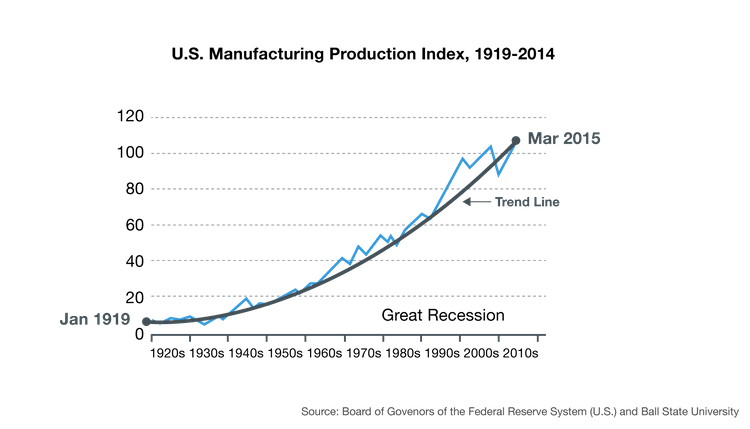

For those who long for the good old days of manufacturing, one expert insists we should view the manufacturing sector as more boom than doom.

“The U.S. manufacturing base is not in decline, and we have recovered from the recession,” Michael Hicks, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University, said in 2015. “Nor are jobs being outsourced because American manufacturing can’t compete internationally. Moreover, new jobs in manufacturing pay well above the average wage.”

A 2015 study by Hicks and colleagues at Ball State found that nearly 88 percent of the job losses in U.S. manufacturing from 2000 to 2010 could be attributed to a boost in productivity, including the improvement of supply chains, the rise in capital investments, and the introduction of cutting-edge technology.

Other experts, however, argue just the opposite. They pin more blame for manufacturing losses on global trade, not increased productivity.

“Ultimately, it is difficult to place full blame on either automation or on trade and competitiveness as the leading contributor to manufacturing job losses, and it is likely that both offer potential explanations,” according to the State Science and Technology Institute.

Manufacturing Jobs of the Future

Whether productivity or trade is behind the shift in the manufacturing sector, new data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts a grim future for manufacturing jobs, which are among those that the agency categorizes under “production occupations.”

The bureau forecasts that this category is the only major occupational group that’ll experience a decline from 2016 to 2026–to the tune of approximately 383,000 lost jobs. What’s the cause of the projected drop-off? The manufacturing sector has become more reliant on technology and less reliant on humans, the bureau explains.

However, manufacturing plants still can’t run by themselves. For example, Flex points out that people will be needed to design, build, manage, program, and maintain robots. Among the new breed of jobs that will come along are robot-monitoring professionals and automation specialists, according to a 2016 report from Forrester Research.

Additionally, people will be needed to develop the software behind automation and robotics.

In an extensive report released in mid-2017, ManpowerGroup and UI Labs’ Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute describe 165 roles that they say will define the digitally driven future of manufacturing. Some of these roles may be inside a factory, while others may be outside the factory walls. Here’s a small sampling of these roles:

- Digital manufacturing chief technology officer, responsible for overseeing the digitization, automation, and connectivity of manufacturing systems.

- Digital manufacturing analyst, responsible for combing through data to unearth potential improvements in manufacturing productivity and product quality.

- Model-based systems engineer, responsible for breaking down complex product concepts into smaller chunks.

- Manufacturing cybersecurity strategist, responsible for helping prevent threats from hackers and other cyber troublemakers.

- Embedded product prognostics engineer, responsible for monitoring a product’s performance and anticipating problems or maintenance needs.

- Virtual reality/augmented reality system specialist, responsible for helping demonstrate a product or process in a virtual setting.

- Predictive maintenance system specialist, responsible for monitoring the health of a critical manufacturing asset and figuring out when it might fail.

- Machine learning specialist, responsible for helping emulate the human decision-making processes related to design and development tasks and decisions.

- Digital twin architect, responsible for creating virtual representations (digital twins) of products, processes, and systems.

- Digital manufacturing technical educator, responsible for teaching students the skills required to succeed in digital manufacturing.

- Digital factory automation engineer, responsible for developing and setting up automation tools that improve manufacturing productivity and product quality.

- Collaborative robotics specialist, responsible for implementing robotics platforms that “collaborate” with humans and for training robotics operators.

- Collaborative robotics technician, responsible for setting up and maintaining collaborative robotics systems.

In an extensive report released in mid-2017, ManpowerGroup and UI Labs’ Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute describe 165 roles that they say will define the digitally driven future of manufacturing.

“The new roles we have identified will help prepare American workers for the technological shift that is underway, providing attractive, well-paying jobs for the next generation of manufacturers,” says Caralynn Nowinski Collens, CEO of UI Labs. “A smart factory is going to be very dependent on this new workforce.”

Forrester Research expects technologies like robots, artificial intelligence, machine learning and automation to eliminate 10 million U.S. jobs–a loss of 25 million jobs offset by a simultaneous gain of 15 million jobs. Office and administrative support staffers will suffer the most harm, Forrester says.

In manufacturing, robotics will affect some segments (and, therefore, some jobs) more than others.

The Boston Consulting Group says four industry groups will account for about three quarters of robot installations around the world through 2025:

- Computers and electronics

- Electrical equipment, appliances and components

- Transportation equipment

- Machinery

On the flip side, the consulting firm predicts a number of industry groups will be largely untouched by robots through 2025, including chemicals, wood products, paper, fabricated metals, food processing, and textile products.

The International Federation of Robotics estimates more than 2.5 million industrial robots will be at work around the world in 2019. Today, the automotive and electronics industries “employ” the most robots among all industrial sectors.

Regardless of how all of this shakes out, it’s much too soon to write an obituary for American manufacturing and American manufacturing workers.

“There’s a widespread belief that U.S. manufacturing is disappearing, and that the United States doesn’t make things anymore. Such impressions are patently false,” IndustryWeek Custom Research and software company Kronos say in a 2016 study.

Software’s Vital Role in Manufacturing

Obviously, robots and other automation methods are driving advances in manufacturing. But at the heart of the automation explosion is software–software to manage the robots, for instance, and software to teach tech skills to workers transitioning from old-school to new-school factory tasks.

A primary example is manufacturing execution system (MES) software, which manages what’s happening on the factory floor and monitors the product, production or work-in-progress. Today, that software monitors the work of humans and machines, including robots. At some manufacturing plants, MES software is being integrated with manufacturing software such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, which helps juggle day-to-day business activities like accounting and HR.

Other types of software that are growing in importance at manufacturing plants include:

- Robotic process automation (RPA) software. Simply put, this software automates manufacturing tasks carried out by people.

- Planning and scheduling software. This product simplifies planning and scheduling by taking into account factors like materials supply, labor availability and production capacity.

- Learning management system (LMS) software. This software is an all-in-one solution for operating workplace education and training programs.

The Education Divide

While Americans still can find–and still will be able to find–jobs in the manufacturing sector, they’re not the types of positions that our grandmothers or grandfathers might have held.

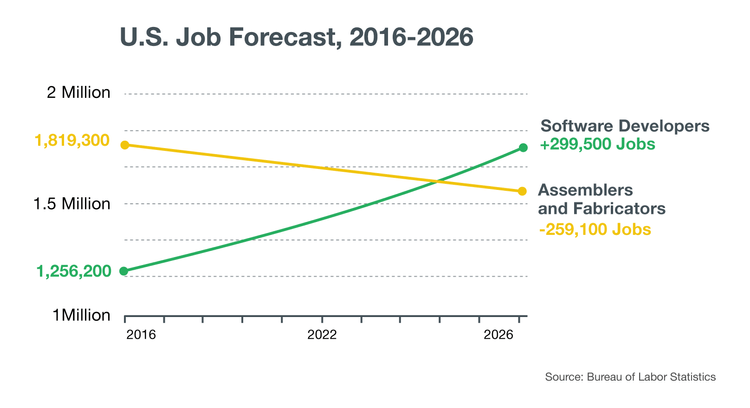

Take, for instance, software developers. They’re a critical component of the automation wave in manufacturing (although a lot of developers don’t work directly for manufacturers). From 2016 to 2026, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts the number of jobs for software developers will jump by 24 percent, leading to the addition of 299,500 jobs.

By contrast, the ranks of America’s assemblers and fabricators–manufacturing workers who put together finished products like aircraft, toys, and electronic devices, as well as the parts for those products–are shrinking. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts the number of assemblers and fabricators will slide by 14 percent from 2016 to 2026, resulting in the loss of 259,100 jobs.

The International Federation of Robotics refers to this phenomenon as a “reallocation” of jobs.

“Concern about the future of employment and jobs is causing widespread debate and political shifts,” the federation says. “Attention has turned to the role of automation, with automation–and robots–more often than not presented as ‘job killers’. But this is not borne out by the facts. Research indicates that robots complement and augment, rather than substitute for, labor and in doing so, raise the quality of work and the wages of those fulfilling new tasks.”

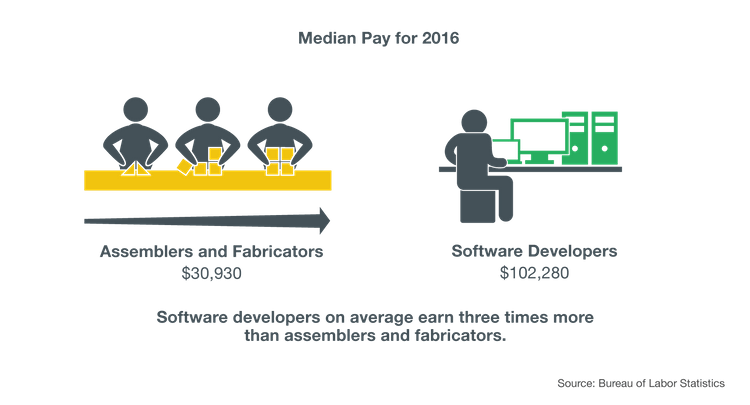

The in-demand manufacturing jobs of the present and the future (such as in-house positions like robot technician and outside positions like software developer) pay far more than Grandma or Grandpa likely ever earned. For instance, the median pay in 2016 for a software developer in the U.S. was $102,280 per year, compared with $30,930 for assemblers and fabricators, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But these higher-paying jobs typically require a higher level of education than Grandma or Grandpa might have had. A lot of tech-oriented jobs in manufacturing demand a bachelor’s degree or some other form of post-high-school learning, whereas a lot of manufacturing jobs from the past might have required no more than a high school diploma, if that.

“Americans being displaced by robots and automation lack critical skills needed in the future economy, and little is being done to support these workers or prepare disadvantaged students,” Brookings Institution scholar Scott Andes warned in 2016.

(Andes maintains that there’s no correlation between “job-stealing robots” at manufacturing plants and job losses in the manufacturing sector.)

To fill the skills gap, a slew of initiatives are underway.

Google, for example, launched the Grow with Google program in October 2017. The program will enable job seekers and entrepreneurs–in manufacturing or any other industry–to obtain free training so they can pick up skills needed to compete in the Digital Age.

“We understand there’s uncertainty and even concern about the pace of technological change,” Google noted in announcing the initiative. “But we know that technology will be an engine of America’s growth for years to come.”

On top of Grow with Google, the company’s Google.org philanthropic arm has committed $1 billion over five years to nonprofits that are striving to beef up workers’ high-tech skills. That includes a $10 million grant to Goodwill, the country’s largest nonprofit dedicated to workforce development.

In their 2014 book, “The Second Machine Age,” MIT scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee underscore the importance of education in today’s workforce (including the manufacturing sector).

The scholars write that “there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education, because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only ‘ordinary’ skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate.”

Conclusion

Just as America evolved from a farm economy to an industrial economy, we’re now morphing into a digital economy from an industrial economy. Obviously, this will mean adjusting our notions about what constitutes a manufacturing job and about how we’ll cultivate a manufacturing workforce that’s ready for the industry’s high-tech transformation.

“Improving the system of digital manufacturing talent will hinge on a better balance between supply and demand, including a fuller pipeline of workforce candidates,” the Manpower/ULI Labs report says. “The old job boundaries, outdated workforce processes, or conventional leadership practices towards the manufacturing organization will grow less and less relevant.”

Over the course of about eight decades, U.S. Army Gen. George Patton, a key figure during World War II; Lee Iacocca, a former leader in the U.S. auto industry; and Mitt Romney, a prominent Republican politician, uttered a quote that applies to the juncture where manufacturing stands today: “Lead, follow, or get out of the way.”

As it pertains to manufacturing jobs, those who lead or follow–and adapt to the digital future–will find work at American factories and the businesses that support them. But those in manufacturing who “get out of the way,” for whatever reason, risk becoming an endangered species.

What does the current technology landscape looks like for SMB manufacturers–and what are their plans for the future? Check out our new report Tools of the Modern Manufacturer.