The Best Accounting Software

We tested the most popular accounting software on the market and cross-referenced thousands of user reviews. We picked our favorite systems below.

- Strong invoicing capability

- Large number of add-ons and integrations

- Free trial available and no setup fees

- Intuitive user interface

- Powerful integrations

- Extensive reporting

- No setup costs

- Discounted intro pricing

- Recurring invoicing

Accounting software tracks financial transactions for reporting and analysis, making it easier to complete audits or analyze information from years prior. Using our review methodology, we picked the top systems on the market.

- Xero: Best Overall

- QuickBooks Online: Best for Small Businesses

- Freshbooks: Best for Freelancers

- CustomBooks: Best for CPAs

- Sage Intacct: Best Mid-Market Software

- NetSuite: Best ERP Option

- Zoho Books: Best for Growing Companies

- Dynamics 365: Best Microsoft Integration

- Odoo: Best Open Source Option

- Striven: Best for Service-Based Industries

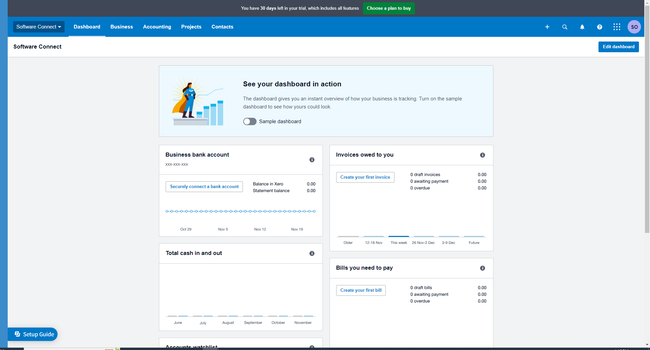

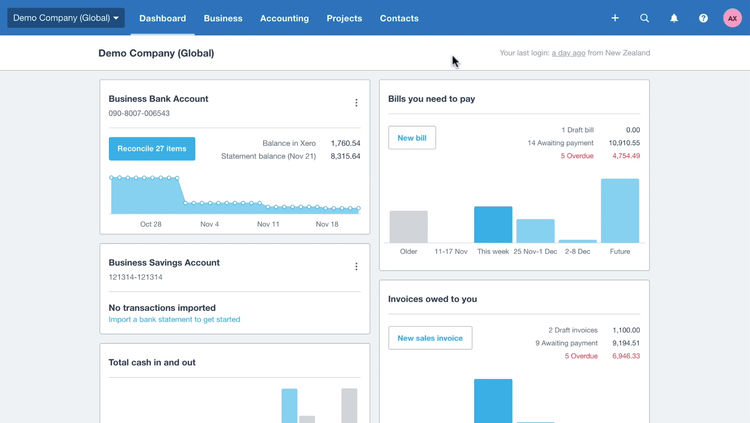

Xero - Best Overall

Xero’s invoicing module gives you plenty of customization options, from adding your company logo to tweaking fonts. But where it really stands out from other accounting software is its advanced invoice templates. While setting them up takes a little extra effort, the flexibility is worth it. You can use Microsoft Word to format your invoices however you like, from adding images to adjusting colors, instead of being stuck with rigid, pre-built templates. From there, it’s as easy as uploading the file to Xero for future use.

Xero also makes recurring invoices simple. You just need to set the start and end date, pick the customer, and add line items. You can also send automated invoice reminders and choose whether to save drafts, approve them manually, or have them auto-send. One thing to note: Xero’s Early plan caps you at 20 monthly invoices, so if you rely heavily on recurring billing, you could hit that limit fast.

Additionally, Xero lets you check stock availability directly within the invoicing screen. If an item is low in stock, the system notifies users before approval so you don’t accidentally oversell. You can then generate a purchase order directly from the invoice to reorder. To speed up payments, you can integrate PayPal, Stripe, or GoCardless, letting customers pay right from the invoice.

Xero starts at $20/month, but most businesses opt for the Growing plan at $47/month for unlimited invoicing and quotes. You’ll need to rely on third-party add-ons like Gusto to run payroll, which is pretty standard for online accounting software like Xero.

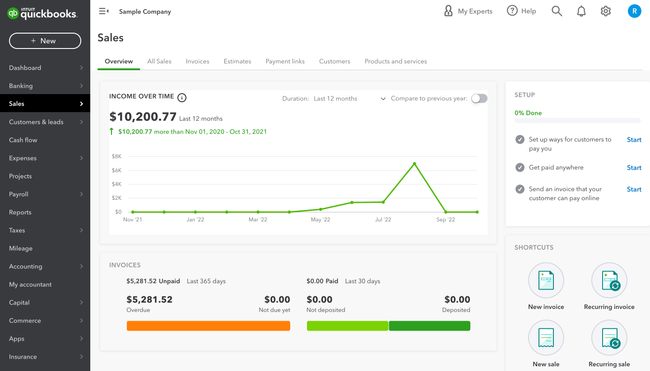

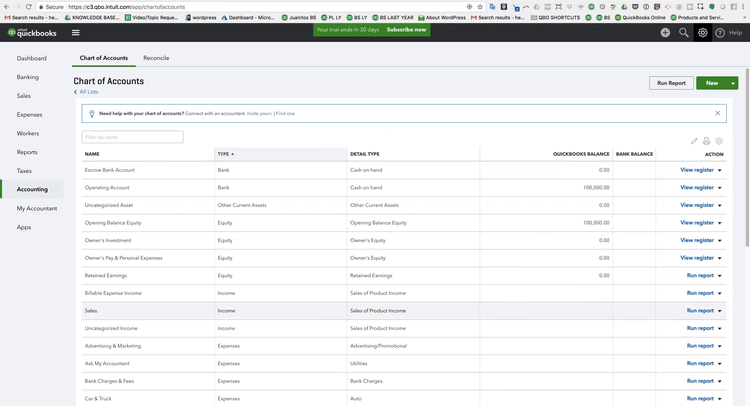

QuickBooks Online - Best for Small Businesses

QuickBooks Online includes extensive integrations and invoicing capabilities. Widely recognized as the most popular financial software, QuickBooks allows companies to invoice an unlimited number of clients, even at basic subscription levels.

It’s relatively easy to track sales and expenses, manage customers, and create estimates. QuickBooks Online also supports collaboration with external accountants. It allows accountants to capture and organize receipts, maximize tax deductions, and process payments. While it may lack industry-specific functions, it remains a solid choice for service-based businesses that don’t require inventory tracking in their books.

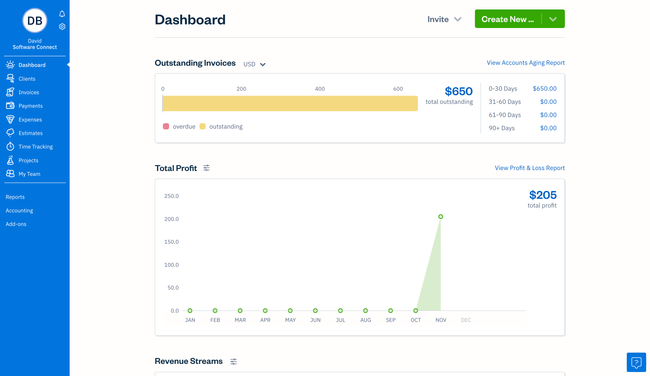

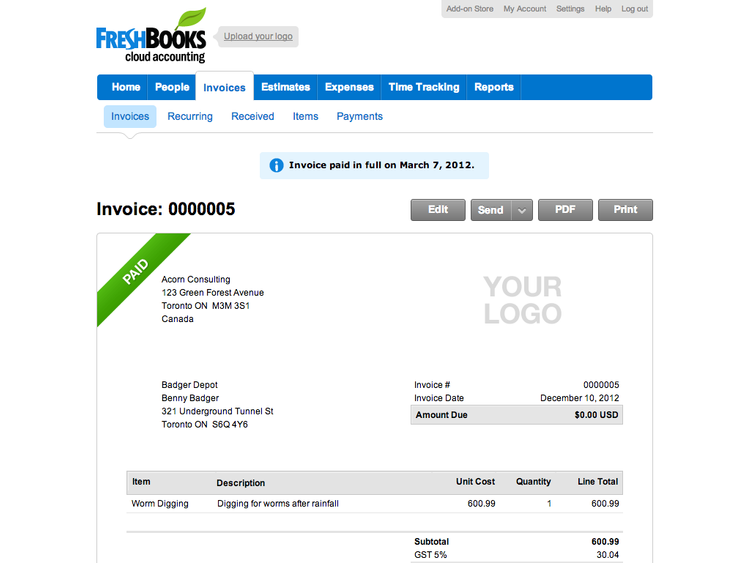

Freshbooks - Best for Freelancers

FreshBooks is best for independent contractors and solopreneurs. Even micro businesses with two to five employees will find the software useful for improving cash flow, invoicing, and time and expense tracking.

We tested FreshBooks for ourselves and found report customization pretty basic. You can change and compare dates and switch from accrual to cash-based accounting. However, it does include 20 built-in reports that help monitor financial health, like profit and loss, general ledger, and balance sheet.

The biggest benefits of FreshBooks are the features included for the price. Rather than offering a stripped-down starter plan, their “Lite” package includes unlimited invoices, expense entries, estimating, and time tracking. With a built-in automated bank import tool, FreshBooks can also accept credit card payments and ACH bank transfers.

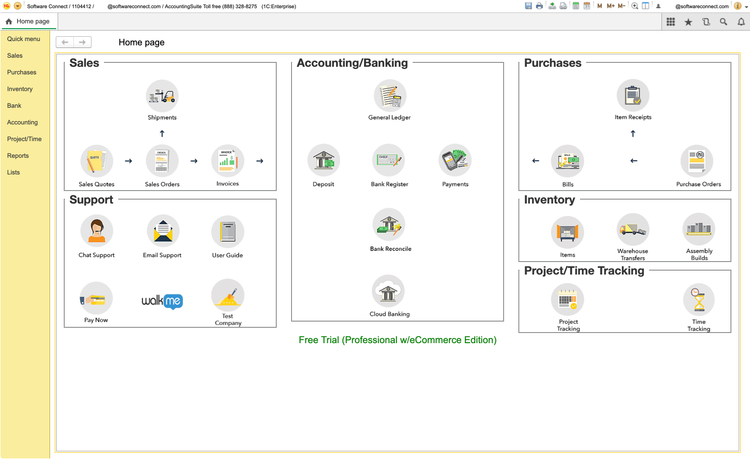

CustomBooks - Best for CPAs

CustomBooks, formerly AccountingSuite, is best for CPAs and small to mid-sized companies with anywhere from five to 500 employees. It automates routine tasks like tax filing, reconciliation, report generation, and account allocations. This allows you to focus on higher-value activities for clients through strategic advising or tax planning.

CustomBooks starts at $19/month; however, the Business plan at $99/month is the best option for invoicing and billing. While the user interface can appear crowded and tricky to navigate, Yellow Labs Software offers an extensive knowledge base to quickly get you up to speed.

Sage Intacct - Best Mid-Market Software

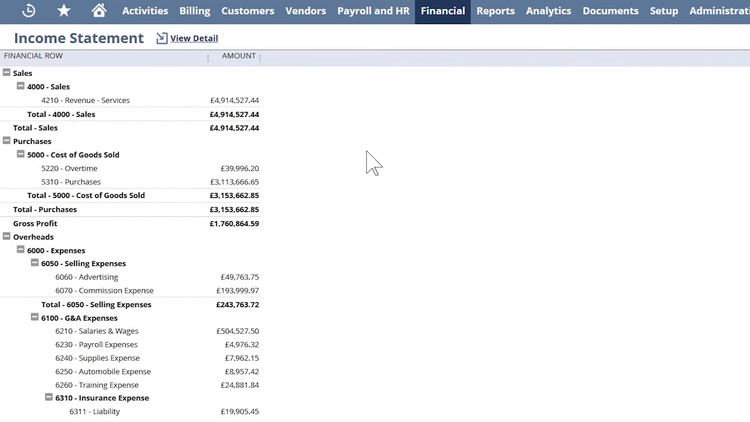

Sage Intacct for companies that have outgrown entry-level solutions like QuickBooks. The software is best for businesses with 15 to 250 employees and $5 to $250 million in revenue. As an ERP system, Intacct includes support for core financials, billing, purchasing, sales and use tax, inventory management, and project accounting.

Most of Sage Intacct’s applications are financial-based, including accounts payable, accounts receivable, cash management, a general ledger, order management, and purchasing. We found its analytical capabilities extensive, with 150 pre-built financial reports. Its interactive custom report writer relies on a drag-and-drop interface rather than coding expertise.

NetSuite - Best ERP Option

NetSuite is well-suited to mid-sized companies with anywhere from 50 to 200 employees. As a full-fledged ERP system, it has built-in modules for HR, inventory control, and procurement, in addition to accounting. Its functionality is pretty extensive, with core capabilities covering everything from general ledger to fixed asset management.

NetSuite is a great fit for global operations. It supports multi-currency transactions and local tax regulations out of the box. It also features 20 pre-built financial report templates. Like Intacct, NetSuite offers a drag-and-drop report builder called SuiteAnalytics. However, creating complex custom reports requires some degree of coding knowledge.

Ultimately, it’s “the world’s most deployed cloud ERP” for a reason. Its cloud-based architecture cuts costs for on-site hardware and expertise.

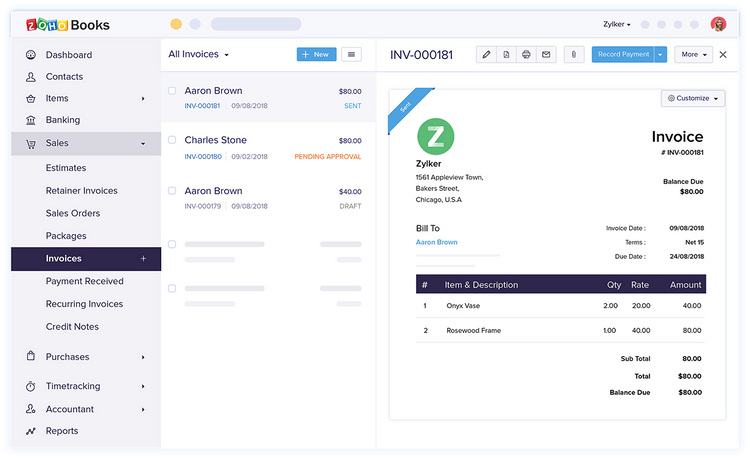

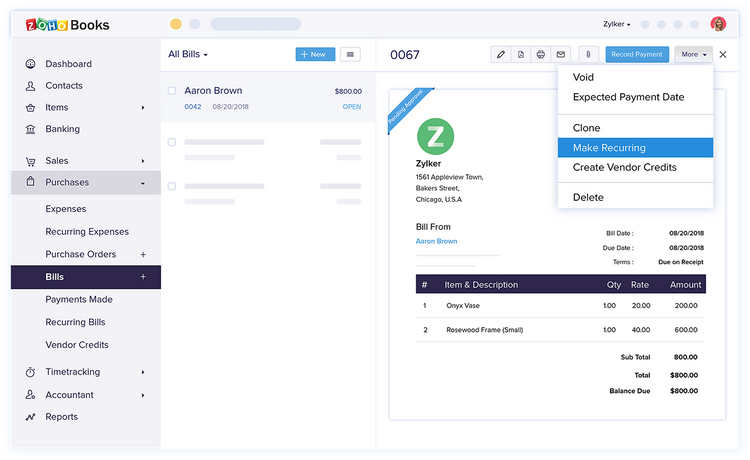

Zoho Books - Best for Growing Companies

Zoho Books supports businesses operating in different countries, offering extensive multi-currency and multi-language capabilities. It integrates with over 10 third-party payment gateways like Stripe, PayPal, and Square, providing flexibility in payment acceptance. This makes it a solid pick for businesses looking to expand or operate internationally.

Zoho Books is known for its scalability, with plans ranging from a free version to more advanced options for mid-sized enterprises. Each plan includes a certain number of users, with the option to add more for a small fee, making it competitive in terms of price and user access. Though the lower-level plans are limited in terms of inventory control, the Standard plan includes 10 custom reports and up to 5,000 invoices per annum.

Dynamics 365 - Best Microsoft Integration

Microsoft Dynamics 365 Business Central is an integrated ERP solution combining finance with operations, sales, and customer service, all under a familiar Microsoft ecosystem. It’s a solid choice for companies needing deep integration with other Microsoft products like Office 365, Power BI, and Azure.

During our free trial of Business Central, we tested a comprehensive array of financial tools, from cash flow forecasting to customizable reporting. Users can also enable predictive analytics and AI-driven insights to better predict future scenarios. That said, accountants will have an easier time with it. For example, it requires an understanding of debits and credits.

Odoo - Best Open Source Option

Odoo provides CRM, sales, and finance apps, including accounting, invoicing, and expenses. While bank synchronization can be a little cumbersome, it’s simple to create—and even mail—invoices in the system.

Odoo offers a free, open-source Community edition without any licensing fees. However, deploying the software and customizing the source code requires technical expertise. Nevertheless, Odoo’s extensive modules and integration options make it highly customizable for SMBs.

Odoo can automate tax calculations based on product categories and locations. Its accounting system supports multiple currencies, which is great for companies serving customers globally. The software also has built-in payment options with popular platforms like PayPal, Stripe, and Buckaroo.

Striven - Best for Service-Based Industries

Striven best serves SMBs in professional services, IT services, legal and law firms, and consulting. It’s an ERP software with functionalities spanning accounting, sales, CRM, and project management. It’s generally the next logical step for businesses needing more functionalities beyond what basic financial software can provide.

Striven delivers a full accounting module, handling AP/AR, general ledger, revenue tracking, billing, and invoicing. The ERP allows companies to personalize invoice templates, making adding their logos, brand colors, and custom fields easy. Though Striven has no native payroll option, it does integrate with payroll providers.

What is Accounting Software?

At a minimum, accounting software tracks financial transactions to record profit loss and improve business finances and overall cash flow. Core functionalities include general ledger (GL), accounts payable (AP), and accounts receivable (AR). Additional functionalities extend to processes like bank transactions, purchase orders, payment reminders, and payroll services.

Many industries require customizable financial management functionalities, such as fund accounting for nonprofits, job costing for construction firms, or DCAA compliance for government contractors. There are also different ways of conducting your accounting process, such as single— or double-entry accounting.

Small business owners may want only to streamline the basics. But in larger organizations, the terms “accounting software” and “ERP” are often used interchangeably. The right software will provide the data management tools needed for accurate account balances and prepare you for tax time.

Key Features

Business accounting software has features and applications that can be divided into basic categories: common (typically found in all accounting software), industry-specific (only found in certain types of accounting software), and advanced features (only used by mid-sized to larger businesses).

While many top accounting software features exist to benefit your business, let’s focus on some of the essentials:

- Core accounting: Cover revenue and expense tracking and create financial reports for your business. Includes accounts payable, accounts receivable, and a general ledger.

- Payroll: Manage employee compensation: wage calculation, direct deposits, check printing, and compensation tax reports.

- Billing and invoicing: Pay bills and create, send, and manage outbound invoices to customers for client work. Attach sales tax figures. Collect customer payments online via credit card or ACH bank transfers.

- Bank reconciliation: Import bank records, often in real-time, and attempt to auto-match bank and accounting records.

- Inventory management: Track inventory as current assets on the balance sheet. Track the cost of goods sold on your income statement.

- Purchase Orders: Create the financial document issued to vendors when buying supplies or services. Includes information such as product type, quantity, and pricing.

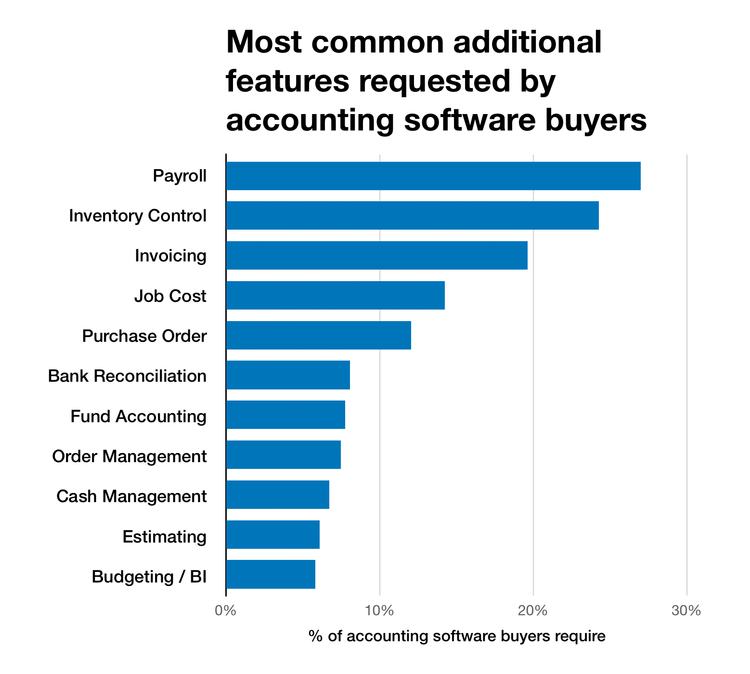

Our recent accounting software buyer trends report found that payroll, inventory control, and invoicing were the most requested features that buyers search for, on top of the "core” accounts payable, accounts receivable, and general ledger.

Primary Benefits

From a small business requiring an off-the-shelf option to a larger enterprise needing a vast amount of customizations, this buyer’s guide will cover everything you should prioritize during your search when reviewing accounting software. The best systems help alleviate pain points from manual methods, but they may also bring about some technological pain points that you’ll want to be prepared for.

Integrations

Companies that do not have comprehensive software will often combine more than one application to meet all of their needs. Off-the-shelf software that handles core accounting may lack functions such as payroll, advanced reporting, or stronger inventory tracking. Once these accounting features are needed, many buyers may lack the means necessary to integrate the programs.

Integrations, or APIs, allow distinct products to talk with one another. For example, your payroll system could update your HR team with a chat program (such as Slack) of any processing errors. Your payment processor might automatically push new receivable entries to your accounting system. Your accounting software could share available funds with business intelligence systems.

Expect inter-software communication abilities to increase in most products. While some accounting products may try to provide an “all-in-one” tool, others will focus on being the best in a few main areas and offer integrations to tools that help complete their program.

Industry-Specific Options

As consumers demand functionality more in-tune with their industry needs, software developers are doing everything possible to make those dreams a reality.

While a super-niche industry may not have a software option exclusively developed for them, they can generally turn to specialized vendors. These companies pride themselves on implementing specific software solutions in specific environments. They generally offer customizations or add-ons for a generic product that will make it more in line with what the business expects on a day-to-day basis.

Custom Accounting Software

Many companies will try to make do with a lower-cost solution at the expense of functionality. Options such as Sage 50c, Zoho Books, and Quickbooks Online are great low-priced options for new businesses, but they’ll lack ways to customize the software towards your business.

Popular accounting software customizations include:

- Tailored reports

- Role-based dashboards

- Custom data fields

The bottom line is, don’t sacrifice functionality for cost if it’s something you may want to add a year from now.

Remote Access With Cloud

Also known as software-as-a-service (SaaS), cloud-based software adoption rates have increased over the past decade. In 2015, 76% of the buyers indicated receptiveness to hosting their software externally, off-premise. In 2017, this percentage rose to 84% and has only continued to rise.

With cloud-based software, products are leased rather than licensed, a more attractive option for smaller businesses with limited funds or short-term needs. The industry has responded by making software more available on a cloud basis.

Mobile Accounting Software

In 2016, mobile web browsing surpassed desktop browsing in user counts. Naturally, usage has translated into business demands for accounting solutions compatible with iOS and Android apps.

Accounting software developers have responded in kind, especially within fields that require on-site analysis, such as construction and field service. This also makes accepting credit card payments in the field easier than ever.

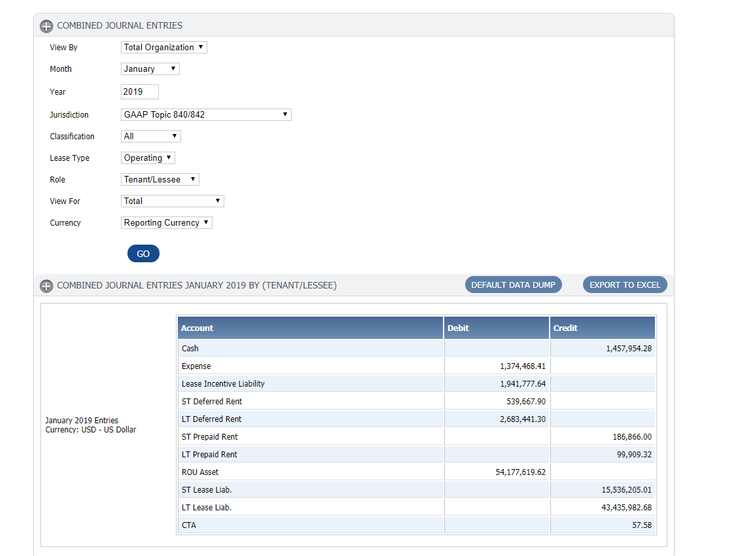

Lease Accounting Standards Update

To improve financial reporting, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued a new standard on lease accounting. Each asset with a 12+ month lease term must be included on a balance sheet. This includes equipment, buildings, vehicles, and other assets your company leases.

The new standard went into effect for public companies for fiscal years and interim periods beginning after December 15, 2018, and for private companies for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2019, and interim periods within fiscal years after December 15, 2020.

Read more on our lease accounting software guide.

What Does Your Business Need?

Creating financial management reports with your data, using mobile apps, finding a new support vendor, or finding the cheapest cloud-based accounting option: everyone has their main motivation for finding a new solution.

The needs and motivations of many buyers will differ from project to project. While many types of buyers exist, most can fit into these common categories below.

Small Businesses

New buyers will likely desire a basic solution that can easily and automatically manage their finances and help them pay bills. 37% of the companies we surveyed were buying accounting software for the first time. Many small business buyers were looking for increased functionality over their current methods, which ranged from a manual bookkeeping method (pen and paper) to a popular starter solution such as Zoho Books or Sage 50c (Peachtree).

Additionally, companies that require many users or manage multiple entities most commonly want small business ERP software with a full suite of functionalities to go along with their accounting.

View the small business accounting software page for options.

Midsized Companies

Over 20% of buyers said they need more software that handles payroll, inventory management, and invoicing. These features are common in enterprise business accounting software. A growing business also has more users in the system, which means needing extended vendor support if your staff isn’t trained properly.

View the midsize business accounting software page for a list of options.

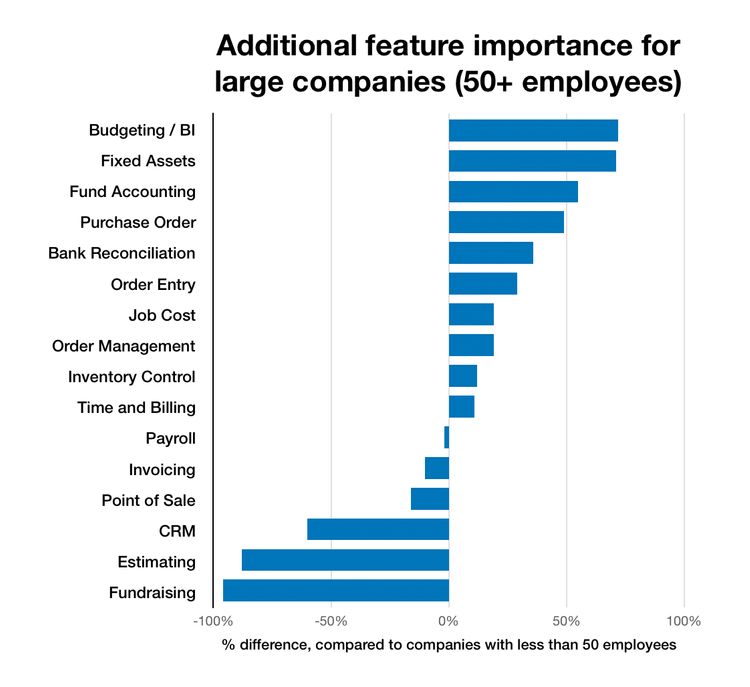

Enterprise Accounting Software

In contrast, more than 70% of larger businesses surveyed desired software that handles advanced budgeting and forecasting or a business intelligence (BI) package for better analytics and financial statements. Larger businesses also desired fund accounting capabilities and a way to manage their procurement.

View the enterprise accounting software page for a list of options.

Outsourced Accounting Services vs. Using a Software In-House

Maybe your business doesn’t need a software system and can get by with outsourced accounting tasks from a local accountant or CPA. While the services offered by these professionals are usually of a higher quality, there are other critical factors to consider:

- Do you have the technical resources to use the accounting tools correctly?

- Are you comfortable managing your business’s financial data beyond simple spreadsheets?

- Does the cost of software outweigh the cost of paying for a firm’s services?

Is QuickBooks the Right Choice?

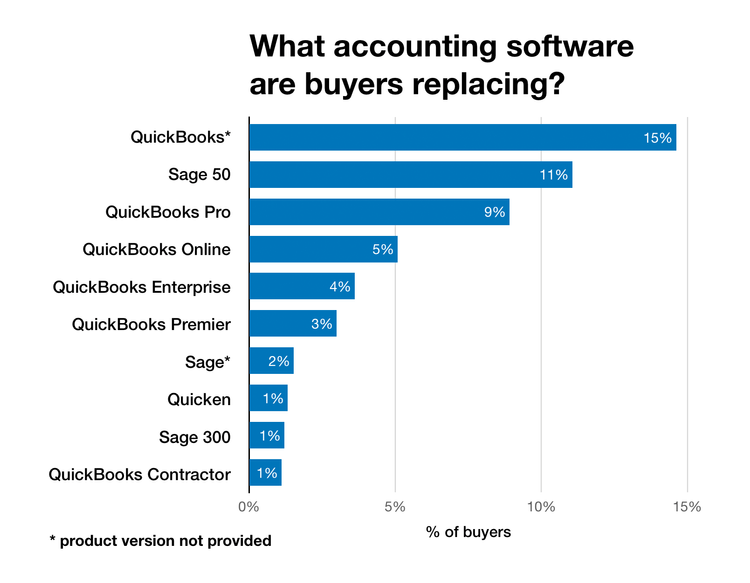

Undoubtedly, QuickBooks is a massively popular accounting solution, particularly among small business owners. While a product such as Intuit QuickBooks Online can serve many needs, it’s also the most commonly replaced accounting software on the market since it lacks more advanced accounting features.

Our previously mentioned buyer trends survey found that 33% of upgraders come from QuickBooks.

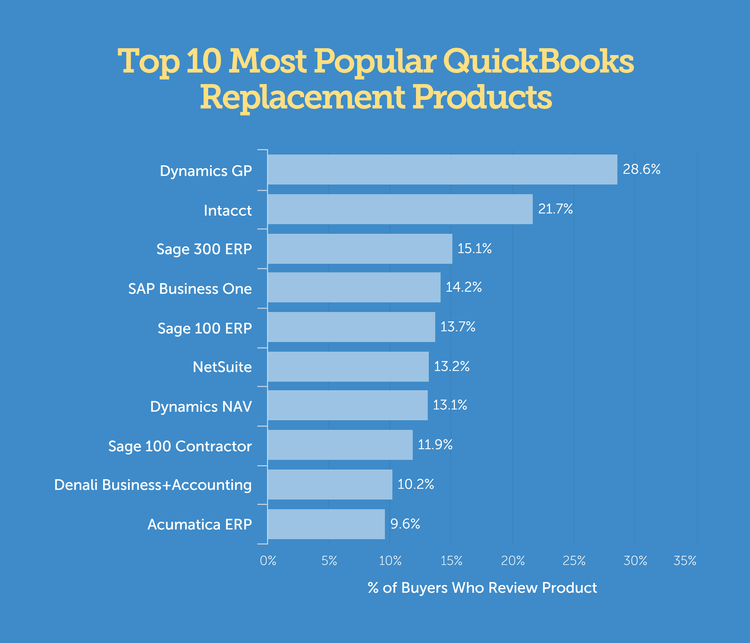

Best QuickBooks Alternatives

Another study on over 4,000 previous users for their most popular replacement products led to a list of suitable Quickbooks alternatives. These will vary by industry, but these options were found to be the most common choices for companies to review:

If you are looking for an alternative small business accounting software that still provides ease of use and an affordable cost, consider these comparable options which offer great sign-up offers, such as:**

You can also check out the best free accounting software for small businesses to find even more cost-effective options.